This spring I will turn 37, which means that for nearly 30-years I’ve been wearing eyeglasses. I got my first pair in early elementary school, when anything that made me different was a cause for embarrassment for me. I switched to contact lenses in high-school and now, like many people, mix and match the two throughout most days. I’m classified as nearsighted, which theoretically means I can see close-up objects but not distant ones; in reality, my eyes are so bad that without my glasses anything farther than a foot away is pretty blurry.

Recently, I went in for an eye exam. The doctor gave me the usual litany of tests: blinded me with bright light, shot puffs of air into my unsuspecting eyes, dilated my pupils so even the faintest light felt like shards of glass, and repeatedly pestered me to determine which of the two lenses was clearer: Option One or Option Two? (As an example of the malevolence of eye doctors, I honestly believe there comes a point when there’s absolutely no difference between the two, yet they continue to demand a decision just to mess with you.)

Afterward, the doctor explained that everything looked good: my prescription hasn’t changed in several years and my eyes look healthy. Leaning back in his chair he said,

“Just so you know, in about two to three years you can expect that your reading vision, particularly in low-light situations, will become compromised.”

Given that these are the only set of eyes I can reasonably expect to have, I found his choice of words rather dire. Compromised. It sounded like something from a spy movie, when a security wall is breached or a special agent goes rogue. I asked for an explanation, and he continued.

“You’ll notice that reading in certain situations will become difficult. This often happens with menus in restaurants or when you’re in bed at night reading by a small lamp. Suddenly you’ll realize that you can’t make out the words clearly. At that point you’ll probably need to get a pair of reading glasses.”

Reading glasses? I intoned, my voice flat as Kansas.

Absently he nodded, and blithely went about filling in forms on my chart.

I will acknowledge that there are times when I feel my age: my body has its daily aches and pains, it doesn’t heal as quickly as it used to, and sometimes when I’m around kids in their early 20’s I feel categorically archaic (especially so when technologies are involved). Still, on the whole I’m in good shape and generally feel pretty vigorous. But all of a sudden, as the blocky capital-E atop the eye chart stared at me accusingly, old age crushed down upon me heavy as an anvil from a Looney Tunes episode.

Reading glasses? I don’t need reading glasses. I’m too young for reading glasses. Besides, if I won’t need them for at least another two or three years couldn’t this asshole have waited and told me then?

I’m well aware that the slope of aging is a slippery one. My mind began to whirl: What’s next, I worried, shoes with velcro? Adult diapers? How long until I perpetually reek of Vick’s Vapo-Rub and take my dinners at 4pm?

These and other, far more caustic concerns flooded my mind. I wanted to revolt, to stake out a stubborn, Beckett-like position and kick back against the world. I’m too young for this!, I thought about yelling at the doctor, as if he were somehow to blame for my eyes’ degeneration.

My mind spun, my insides churned. I had simply come in for a mandatory eye exam and suddenly I was being confronted with own impending mortality.

I caught myself. Inhaled deeply. Tried to remember good things, like how happy I was playing Frogger as a child. Slowly, my breath stabilized. My qi became unblocked, I cultivated healthy prana, etc.

Eventually, calmed by the thought that the doctor said I wouldn’t notice these changes for several years, I carried on with my day. And that right there is an all-too-clear window into my life-problem-solving-skills, the basic tenet of which is: whenever possible, dodge. I walked out of the doctor’s office and spotted something shiny, and within moments forgot how decrepit I’d earlier felt.

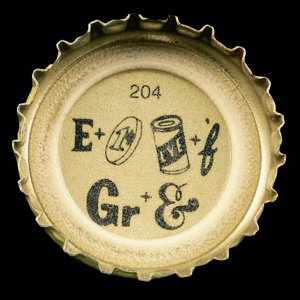

That evening I drove to work, my sharp clear eyes guiding me safely through the city’s traffic. I work at a restaurant, which like many restaurants isn’t the brightest environment, and that evening a table ordered several Rainier beers. Inside the caps of these bottles are printed rebuses, which are those tiny picture-puzzles you have to decipher.

I passed by the table and asked if they’d managed to decrypt the puzzles. They had figured-out several but had been stumped by one. They handed me the cap and asked me for my input.

I held the cap between my fingers and looked down, only to realize that even though I had unconsciously begun to squint at the cap, I couldn’t make out a damned thing on it.

The conversation with the doctor earlier in the day flooded back over me and I began to drown on my own anxieties. He’d said two or three years, and here it was eight hours later and my eyes had already turned against me.

I contemplated a steak knife that was sitting on the table and thought of Oedipus, who, horrified by his surrounding reality cut out his own eyes. Then I thought of Jesus’ admonition to pluck out your eye if it causes you to sin. Neither of these brought me much comfort. For a moment I dreamed of grabbing a beer bottle and returning to the eye doctor’s office, where I imagined myself smashing him upside the head for having placed this horrible curse upon me.

In the end, I took the bottle cap over to a light and was able to read it clearly. But as the night continued I felt all the stuff you’d expect, my mind riddled with the fruitless and petty bargainings one offers against the un-bargain-able.

As I sit now in my night-dark apartment and write on this computer, in tiny font against a sapping background, I find that I can see everything just fine. Someday soon that may change. It might be in two years or maybe it’ll be next week. And so what? I can’t stop these things, and frankly life will go on even if I need to put on a pair of glasses to read. I won’t love it, but I don’t think you’re supposed to, nor do I think it matters.

Some parts of aging are great: I’m actually becoming a somewhat interesting person as I get older, and there’s promise that someday I may contribute something of value to society. But other aspects of it—this, in specific—suck. Gurus teach that one of life’s most important lessons is learning to accept changes when they come. In that regard I think I’m doing okay, or at least I feel obligated to tell myself that. Fiction or not, I suppose it’s the best that can be done.